I stumbled across what seemed an interesting article in Scientific American recently ‘Have Fruits and Vegetables Become Less Nutritious?‘ in which the writer suggests that ‘soil depletion‘ has over the past seventy years lead to a large decline in the vitamin and mineral content of shop bought fruits and vegetables. There are several studies in past decades that found this nutrient decline to be true in both the UK (Anne-Marie Mayer, 1997 [2]) and the US (Donald Davis – University of Texas 1999 [1]).

Initially this soil depletion idea seems to make sense, after all farmers keep farming the same land, extracting more and more produce for an ever increasing population. As somebody more easily drawn to ‘organic’ methods of growing produce I’d probably also like to believe I can blame it on modern agricultural methods. However, when you really look into this matter it’s not very likely that soil management is to blame at all, after all farmers load their fields with fertilisers.

If not soil depletion then what?

Since World War Two, in the face of an ever increasing population and higher demand for fruits and vegetables there has been a drive to increase crop yields. Much has been much done by plant breeders to produce commercial plants that are bigger and stronger, more resistant and more consistent in appearance at harvest time. However, it appears that whilst it is possible to develop these bigger yielding varieties there is not a corresponding increase in the percentage of minerals and vitamins contained within them at harvest time.

Genetic Dilution

The cause of this inverse relationship is something called genetic dilution – you can grow a bigger variety of broccoli but you won’t get more of the good stuff inside it. A suggested reason for this includes a trade off between plant resources; just because a plant is bred to be big doesn’t mean that the root system has also developed in line to give an equivalent proportion of absorbed nutrients. As a consequence you could buy a large swede in the supermarket today and find it has the same vitamin and mineral content as a small swede would have done fifty years ago, you’re just eating more water and carbohydrates.

Too Much Fertiliser

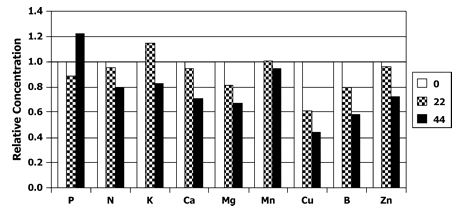

It’s also not only about genetic dilution; it turns out that if you fertilise a plant beyond a certain level (which will vary by species) you may get a bigger plant containing more phosphorus but you still won’t get more minerals and vitamins. Consequently in tests, as a proportion of plant material from our modern higher yielding and heavily fertilised plants, the vitamins and minerals show up in much lower proportions compared to the lower fertilised ‘heirloom’ seed varieties of yester-year. This despite the fact that there are probably the same physical quantities of vitamins and minerals as fifty years ago. In the graph below you can see a raspberry fertilisation test (Hughes, M., Chaplin, M.H., Martin, L.W. (1979) [4] and where more phosphorus is given (black bars) plants get bigger but don’t take on additional nutrients.

So what does this mean?

In essence what this all means is that supermarket fruits and vegetables may be bigger and heavier than ever today due to selective plant breeding and industrialised farming / fertilisation techniques, but they are really no healthier for you to consume than smaller varieties were one hundred years ago. It also means that when we harvest our allotment produce and compare it to the size of the supermarket produce it really makes little difference in nutritional health terms to have smaller results.

Supermarket fruits and vegetables are also stored longer and sent further distances around the world (further exacerbating nutrient decline) and are generally chemically treated vs your lovely organic allotment produce. If you want to maximise nutritional values from your allotment, plant heirloom seeds instead of hybrid seeds and don’t worry too much about produce size (except for show of course…). See my article on F1 vs Heirloom seeds for more information on that topic.

[hr gap=”10″]References

- Changes in USDA Food Composition Data for 43 Garden Crops, 1950 to 1999 (Donald Davis – University of Texas 1999)

- Historical changes in the mineral content of fruits and vegetables, British Food Journal Anne-Marie Mayer, 1997

- Are Depleted Soils Causing a Reduction in the Mineral Content Of Food Crops?

- Declining Fruit and Vegetable Nutrient Composition: What Is the Evidence?

- Dirt Poor: Have Fruits and Vegetables Become Less Nutritious?