Can you imagine being a gardener drafted into a war? You’ve spent each working day looking at nature, admiring her beauty, nurturing life, sowing and growing plants, then suddenly you’re shipped off to a living hell of death and destruction and asked to kill. This is exactly what happened to my great grandad George Cook and many other gardeners during the Great War 1914-1918. George had been a gardener at Tilgate (Crawley) since he was seventeen years of age but ten years later he was fighting at the Somme and Passchendaele. The impact of World War One on British gardens was enormous, at Heligan for example twelve gardeners left for the war and only three survived to return. The Royal Botanic Gardens Kew lost nineteen members of staff to the war.

As a married family man George was conscripted in June 1916, two years into the war. Up until that time fighting was largely the domain of the single man. This undoubtedly saved George’s life because had he joined the 13th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment any earlier he would have been with them on ‘The Day Sussex Died’ – the infamous (and arguably pointless) Battle of the Boar’s Head (June 30th 1916) where almost the entire 13th Battalion of men were killed. Instead he began his training at Chichester and later moved to a camp near Aveley in Essex. It was here on the night of 2 September 1916 that he witnessed the shooting down of the German Zeppelin airship bomber, here he recalls the experience (I love how he says “middle-night” rather than midnight):

Later that month George went off to France to fight at the Somme, he was slightly injured at the Battle of the Ancre (Thiepval) on 13th Nov 1916 but quickly recovered and returned to the front line. In 1917 he was however more seriously injured, this time at Passchendaele (the Third Battle of Ypres), specifically The Battle of Pilckem Ridge on 31 Jul 1917 (St Julien).

“You have never seen such a place, it rained so hard the water couldn’t run away, as soon as the shell holes were made they were full of water.” – George Cook

It was at St Julien that George encountered a young injured German solider in an enemy trench and I like to think this is where the gardener in him kicked in. Rather than shooting him dead, as many would in the height of war, he dressed the soldier’s wound with a bandage before being told to go away!

This treatment might seem like odd behaviour for a man seeing comrades cut down with unexpected shells and machine gun fire each day, but it seems to me that the men behind the fighting retained some of their humanity on both sides. It was common for German prisoners to be used as stretcher bearers behind Allied lines. I found this photograph from the very same battle (Pilckem Ridge) showing German soldiers carrying an injured British soldier.

Party of German prisoners carrying a British stretcher case over difficult ground on Pilckem Ridge, 31 July 1917. Copyright: © IWM.

Perhaps on some level my great grandad had become accustomed to seeing the Germans as not only the enemy but as human beings capable of giving as well as taking life. Maybe that’s why, combined with his background as a gardener and nurturer of life, he took pity on the wounded German soldier.

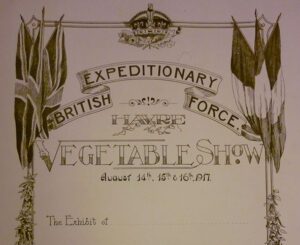

In the midst of the carnage many gardeners did still find opportunities to encourage new life by growing plants. There are tales of trench gardens (on both sides) which no doubt provided food as much as a mental escape from the awful reality of trench warfare. In August 1917 at Le Havre Military Base there was even a vegetable show, it was so successful that it was repeated again in 1918. Of course this was no front line military base under fire from German shelling, it was a supporting base with Convalescent and Rest Camps. Gardening was actively being encouraged by medical staff, horticultural therapy may not be such a modern concept after all!

Eventually, after a return to the Somme and the Battle of St Quentin (22 Mar 1918) George picked up Dysentery due to the poor conditions in the trenches and was hospitalised again. This time he was sent back to England to recover and the war was almost over by the time he was well enough to return to France. It is quite a miracle that between his numerous battles at the Somme and Passchendaele, he wasn’t killed. He lost two brothers, William Cook and Charles Cook, they are remembered on the Menin Gate and Thiepval memorials (as their bodies were never identified). Obviously had George been killed, neither my grandad, mother, me nor my children would exist.

This weekend, as we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the end of the Great War I think it’s important to remember not only the millions who died fighting but also the millions who weren’t born afterwards as a consequence. All those gardeners who didn’t return and all those would-be gardeners who were never born and taught to celebrate life through life itself. I am extremely thankful that for me that chain has not been broken, that I was given the gift of gardening through my parents, grandparents and great grandparents. I have a lot of planting to do in the coming days but as I place each bulb and plug I will be sure to think about the Great War’s Lost Gardeners.

3 Comments

Interesting blog.

So thankful for those men from all walks of life who fought and died for our tomorrows. We must never forget.

A debt

by Shirley Anne Cook

So much depended

on those men: husbands,

fathers, sons, exchanging

pickaxe, plough

and pen for gun.

So much depended

on those men, red-eyed,

voiceless, from gas and cold,

shell-shocked

sleepless nights:

slaughtered,

not grown old.

So much depended

on those men

advancing in rapid rifle rain,

the final whistle,

a final push:

those who returned

never the same.

So much depends –

on us remembering.

(November 2018)

How curious, I’ve been thinking exactly along these lines myself! My great-grandad was a Market Gardener in Catshill, Worcestershire, and was killed in Messines, Belgium, in 1917, and buried, somewhat ironically, at Bethleem Farm cemetery. I’ve visited his grave a few times and am always struck by how beautiful and calm this spot is now – it’s still a farm – and the thoughts that must have been going through his head. I’ll be thinking of him again when I’m on my allotment today. Thanks for a great and thoughtful article.

My Grandad came home from WW1. He wasn’t an employed gardener but had a wonderful allotment I remember. I think of him a lot more as I get older,especially when im in my garden.