Ever wondered what the Jack and the Beanstalk giant meant when he said “I’ll grind his bones to make my bread”? It’s an odd line when you think about it. Is he going to crush the bones of an Englishman into powder and add it to his dough ingredients? Perhaps the giant is actually quite a keen horticulturalist and planning to use the bones as a fertiliser to help grow the wheat for his bread? He’s produced his own giant beanstalk seeds after all so he must know a fair bit about gardening.

As it happens, the giant’s fairy-tale intentions are no more gruesome than the real world activities of the British during the 19th century. The fee-fi-fo-fum poem was written in 1890 after a long period of agricultural bone use, both animal AND human. This bone fertiliser undoubtedly led the public to connect it to wheat production and seems to have officially started after the Napoleonic wars.

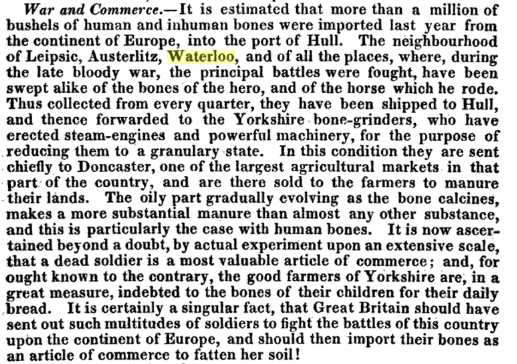

According to quarterly magazine ‘The Investigator’ (Q1 1823 edition), in 1822 one million bushels of bones (about eight million gallons) were shipped from France to Hull in East Yorkshire before being ground up and sent to Doncaster for sale as an agricultural fertiliser. These bones were retrieved from the Napoleonic battlefields of Leipsic, Austerlitz and Waterloo. They were not just the bones of horses killed in action but also included the bones of dead soldiers. Indeed the same article goes on to tell us that human bones make the best manure! Yorkshire seems to have been the main recipient of this gruesome cargo of fertiliser which was spread across the land.

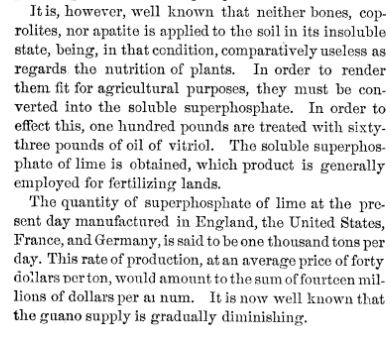

By the middle of the 19th century a chap called John Lawes discovered that natural bone meal wasn’t that useful for crop growing compared to bones treated in acid. Bones are very slow to decompose on their own and this is of little benefit in providing available phosphorus to plant roots. In 1842 Mr Lawes actually patented the process of making super phosphate, proving that compared to natural bone meal it doubled his crop yields and was a far superior turnip fertiliser.

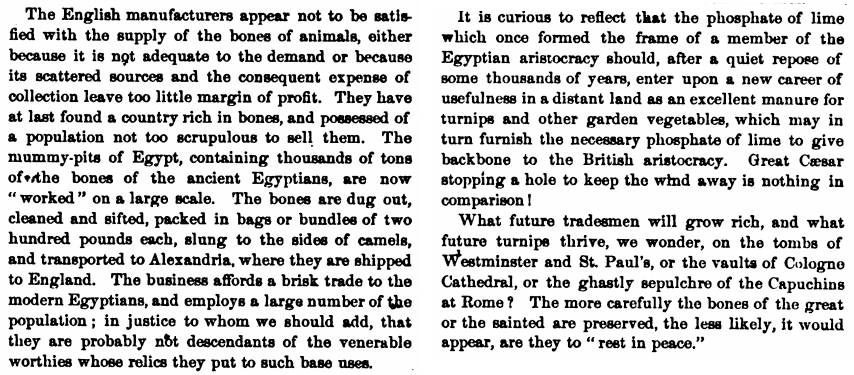

The invention of super phosphate only increased the demand for bones of course and, not satisfied with using the bones of our own soldiers, the British eventually began to import bones from mummies discovered in Egypt! The 1870 edition of American magazine ‘The Manufacturer and Builder’ gives a damning account of the British with their bone harvesting:

According to additional research, as engineers laid the railway line between Cairo and Alexandria they kept discovering the tombs of Egyptian mummies. The mummies were shipped to Alexandria where the cloth was shipped to the rag trade and the bones to England to make fertiliser. In addition to the human bones large volumes of mummified cats were also imported and auctioned off, an example of that being recorded in Liverpool in 1888 (gathered from an enormous feline tomb in the desert of Beni Hassan).

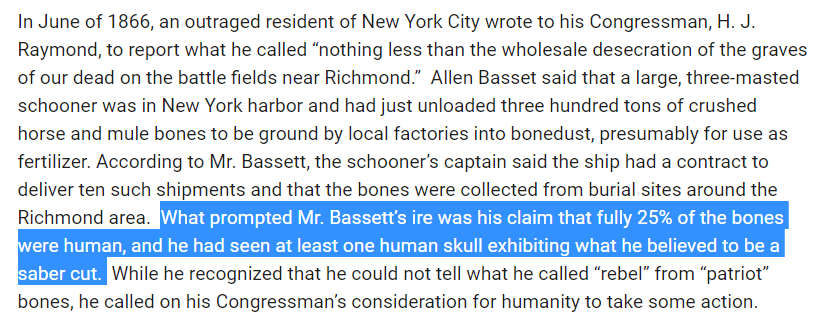

Thankfully the making of fertiliser from soldiers wasn’t limited to us in Britain, despite the condescending tone of ‘The Manufacturer and Builder’ I have bad news for them (if I could deliver it). After the American Civil War human bones were also being harvested from some battlefields. Not officially of course, but permits were granted to collect animal bones and it is inevitable that human bones were also collected. Indeed an account written up in the National Museum of Civil War Medicine says:

Is bone meal good for plants?

The efficacy of bone meal as a plant fertiliser is by all accounts restricted by the acidity of the soil on which it is spread. The University of Colorado more recently found that alkaline soils with a pH of 7.5 and higher typically have a high calcium concentration that binds Phosphorous as calcium-phosphate creating an insoluble compound that is not available to plants. What does this mean? It means that on alkaline soils the application of bone meal is pretty pointless, especially given that it is more likely to encourage some animals to come and dig up the garden.

One wonders if on some level acidic soil provides conditions a little more like those invented by John Lawes with his acid experiments to make super phosphate. Perhaps acidic soil also speeds up the decomposition process allowing plants faster access to phosphorous? Interestingly the soils of Yorkshire, where you’ll remember the bones of our Waterloo dead were spread, are typically more acidic than alkaline (peat based moorlands) and maybe that’s why there was much higher demand for bones by farmers growing plants there?

Of course today one would hope that the bone meal fertiliser products on sales to us at the garden centre are free of human bodies! Instead they should consist entirely of ground and treated animal bones. There was concern a few years ago that the fine powder of bone meal might be inhaled by gardeners and pass on BSE (Mad Cow’s Disease) but modern EU standards say that if the bone meal production reaches 133°C/20’/3 bars or equivalent it should (but not definitely) eliminate any BSE or scrapie agents. It is a little worrying because these agents, known as ‘Prions’ can actually pass into plants and therefore spread diseases like BSE – but there have been no proven cases of that occurring in humans as yet.

I have to say that given the apparent pointlessness of applying bone meal to alkaline soil it doesn’t seem worth investing in it or taking any risks in using the stuff. The efficacy of bone meal in the garden is, like Jack and the Beanstalk, something of a fairy tale for most of us, save your cash.

[hr gap=”5″]